Alighiero Boetti Italian, 1940-1994

Alighiero Boetti (1940-1994) – or Alighiero and Boetti as signed in 1971 – was born in Turin where he made his debut in the Arte Povera in January 1967.

In 1972 he moved to Rome, a context closer to his predilection for the South of the world. Already in the previous year he discovered Afghanistan and started the artistic work he entrusted to the Afghan embroiderers, including the Maps, the colored planispheres that he will propose over the years, as a register of political changes in the world.

A conceptual artist, versatile and kaleidoscopic, he multiplies the types of works whose execution – in some cases – is delegated with precise rules to other subjects and other hands, following the principle of ‘necessity and chance’: so the Biro (blue , blacks, reds, greens) in which the dotted pattern depicts language; thus the embroideries of letters, small or large, and multicolored; or the Tutto, dense puzzles in which heterogeneous silhouettes are found, including shapes of objects and animals, images taken from magazines and printed paper, and much more, really ‘everything’ (Tutto in italian).

Alighiero Boetti has exhibited in the most emblematic exhibitions of his generation, from When attitudes become form (1969) to Contemporanea (1973), from Identité italienne (1981) to The Italian Metamorphosis 1943-1968 (1994). He was present several times at the Venice Biennale, with a personal room in the 1990 edition, a posthume tribute in 2001 and a large exhibition at the Cini Foundation in the recent edition of 2017.

Among the most significant exhibitions of the last few years the great Game Plan retrospective has been realized in three prestigious locations: MOMA in New York, Tate in London, Reina Sofia in Madrid.

-

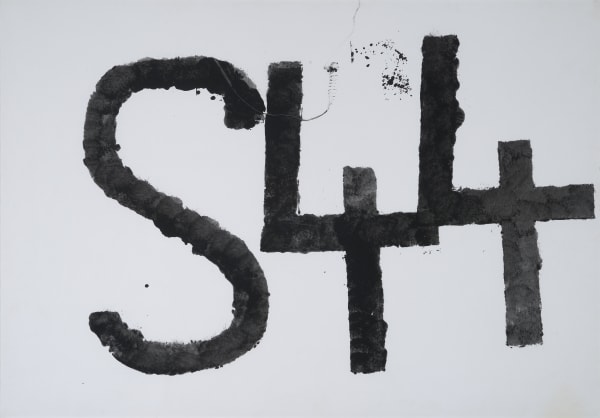

Dodici forme dal 10 giugno 1967, 1971

Dodici forme dal 10 giugno 1967, 1971 -

Immagine somiglianza, 1975

Immagine somiglianza, 1975 -

La meta', il doppio e l'unita' mancante, 1975

La meta', il doppio e l'unita' mancante, 1975 -

Dare tempo al tempo , 1979

Dare tempo al tempo , 1979 -

Turbi e disturbi, 1979

Turbi e disturbi, 1979 -

Untitled (Ordine e disordine), 1979

Untitled (Ordine e disordine), 1979 -

Il progressivo svanir della consuetudine, 1980-1990 ca.

Il progressivo svanir della consuetudine, 1980-1990 ca. -

Immaginando tutto..., 1988

Immaginando tutto..., 1988 -

Inaspettatamente, 1988

Inaspettatamente, 1988 -

Le infinite possibilità di esistere, 1989 ca.

Le infinite possibilità di esistere, 1989 ca.

-

Esprit de géométrie

25 May - 23 Jul 2021ML Fine Art is pleased to announce the upcoming exhibition Esprit de géométrie, from May 25 to July 23 2021, in via Montebello 30, Milan. The show explores the connection...Read more -

From Word to Sign: Accardi Basquiat Boetti Capogrossi Kounellis Novelli Perilli Twombly

curated by Maria Albani 16 Jul - 30 Oct 2020MILAN - ML Fine Art - Matteo Lampertico invites you to discover our online exhibition focused on the relationship between painting and writing, showcasing selected works by Carla Accardi, Jean-Michel...Read more -

Black & White: gesture and geometry in post-war abstraction

9 May - 21 Jun 2019M&L Fine Art is pleased to present a group exhibition of monochrome works by nine Italian and international post-war artists. Encompassing a range of mediums and techniques ranging from the...Read more -

Homage to the square

20 Apr - 26 Jun 2015“Homage to the Square” is the title chosen by Josef Albers for all his works after 1950. These works comprise over one thousand paintings, all absolutely square in shape, in...Read more

Alighiero Boetti was born in Turin in 1940, to Corrado Boetti, a lawyer, and Adelina Marchisio, a violinist. Boetti abandoned his studies at the business school of the University of Turin to work as an artist. Already in his early years, he had profound and wide-ranging theoretical interests and studied works on such diverse topics as philosophy, alchemy and esoterics. Among the preferred authors of his youth were the German writer Hermann Hesse and the Swiss-German painter and Bauhaus teacher Paul Klee. Boetti also had a continuing interest in mathematics and music.

At seventeen, Boetti discovered the works of the German painter Wols and the cut canvases of Argentine-Italian artist Lucio Fontana. Boetti’s own works of his late teen years, however, are oil paintings somewhat reminiscent of the Russian painter Nicolas de Staël. At age twenty, Boetti moved to Paris to study engraving. In 1962, while in France he met art critic and writer Annemarie Sauzeau, whom he was to marry in 1964 and with whom he had two children, Matteo (1967) and Agata (1972). Working in his hometown of Turin in the early 1960s amidst a close community of artists that included Luciano Fabro, Mario Merz, Giulio Paolini, and Michelangelo Pistoletto, among others, Boetti established himself as one of the leading artists of the Arte Povera movement.

From 1963 to 1965, Boetti began to create works out of then unusual materials such as plaster, masonite, plexiglass, light fixtures and other industrial materials. His first solo show was in 1967, at the Turin gallery of Christian Stein. Later that year participated in an exhibition at Galleria La Bertesca in the Italian city of Genoa, with a group of other Italian artists that referred to their works as Arte Povera, or poor art, a term subsequently widely propagated by Italian art critic Germano Celant.

From 1974 to 1976, he travelled to Guatemala, Ethiopia, Sudan. Boetti was passionate about non-western cultures, particularly of central and southern Asia, and travelled to Afghanistan and Pakistan numerous times in the 1970s and 1980s, although Afghanistan became inaccessible to him following the Soviet invasion in 1979. In 1975, he went back to New York.

Boetti disassociated himself from the Arte Povera movement in 1972 and moved to Rome, without, however, completely abandoning some of its democratic, anti-elitist, strategies. In 1973, he renamed himself as a dual persona Alighiero e Boetti (“Alighiero and Boetti”) reflecting the opposing factors presented in his work: the individual and society, error and perfection, order and disorder. Already in his double-portrait I Gemelli begun in 1968 and published as a postcard, Boetti had altered photographs so that he appeared to be holding the hand of his identical twin. He trained himself to write and draw ambidextrously.

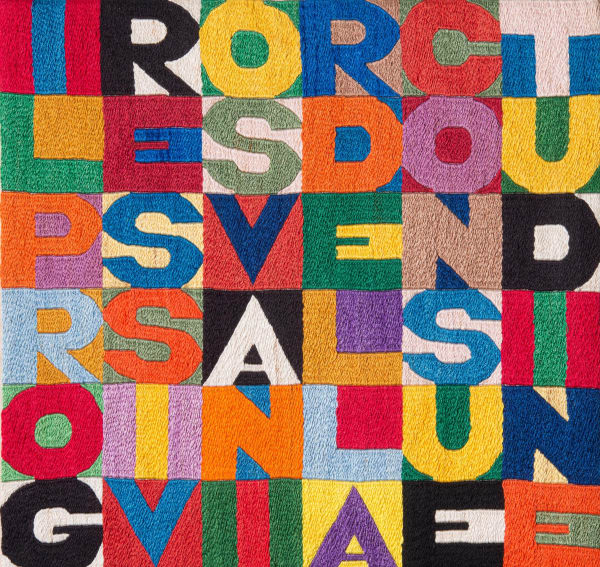

Boetti often conceived of an idea for a work of art but left its design and execution to others. He thus often collaborated with both artists and non-artists, giving them significant freedom in their contributions to his works. For instance, one of the better known types of his works consists of coloured letters embroidered in grids (“arazzi”, meaning wall hangings or tapestries) on canvases of varying sizes, the letters upon closer inspection reading as short phrases in Italian, for instance Ordine e Disordine (“Order and Disorder”) or Fuso Ma Non Confuso (“Mixed but not mixed up”), or similar truisms and wordplays. To create these pictures, Boetti worked with artisan embroiderers in Afghanistan and Pakistan, to whom he gave his designs but increasingly handed over the process of selecting and combining the colours and thus deciding the final aesthetic look of the work.

Boetti’s is best known for his series of large embroidered maps of the world, called simply Mappa. Boetti’s maps reflect a changing geopolitical world from 1971 to 1994, a period that included the collapse of the Soviet Union and the fall of the Berlin Wall. Embroidered by up to 500 artisans in Afghanistan and Pakistan, the maps were the result of a collaborative process leaving the design to the geopolitical realities of the time, and the choice of colours to the artisans responsible for the embroidery. The maps delineate the political boundaries of the countries; some nations, such as Israel, are not represented because the Taliban regime of Afghanistan did not then recognise their existence. When embroiderers ran short of a particular color thread and had to substitute another, oceans came out yellow or red instead of blue. In one map, the sea is unexpectedly coloured pink rather than blue, as landlocked Afghans had no tradition of mapping, certainly not of oceans. The border texts contain dates or details relative to the work’s production, Boetti’s signature and sayings, as well as excerpts from Sufi poetry.

“For me the work of the embroidered Mappa is the maximum of beauty. For that work I did nothing, chose nothing, in the sense that: the world is made as it is, not as I designed it, the flags are those that exist, and I did not design them; in short I did absolutely nothing; when the basic idea, the concept, emerges everything else requires no choosing.” Alighiero e Boetti, 1974.

The brightly coloured Arazzi works are embroidered pieces made in various sizes that depict sentences drawn from poetry, wisdoms from around the world, or sayings invented by Boetti himself. The Arazzi grandi, containing messages in both Italian and Persian, are each distinct, recording the date when they were created, and containing an elaborate internal code that prescribes the order of the sentences on display. They contrast geometric European letters and flowing Persian calligraphy in checkerboard patterns, alternating bands, grids or cruciform shapes. The dates, carefully noted on each Arazzi grandi, mark a point of captivation for Boetti, as he was deeply interested in the concept of time and its inevitable passing. The embroidery of each map normally took one to two years and, in some cases, much longer due to geopolitical events. Following the closure of the Afghan border, Boetti was forced to abandon this practice and work remotely from Italy. This work began in his studio in Rome, with the artist outlining the countries in felt-tip pen onto linen, before sending the cloth framework to Afghanistan. The invasion of Afghanistan by Russian troops in 1979 shifted production completely from Kabul to Peshawar in Pakistan, where the group of Afghan women had taken refuge and where Boetti was only able to reconnect with them through middlemen. It also halted production completely until 1982, with only a few maps being made between 1982–1985.

During the 1980s Boetti visited Pakistan to meet the men organising the embroidery. As a European male, however, Boetti was not allowed to visit the camps. He therefore asked photographer Randi Malkin Steinberger, with whom he had collaborated on the book Accanto al Pantheon in Rome, to go to Peshawar in 1990 to photograph the craftswomen at work. A chief example of this series, Mappa del Mondo, 1989 (“Map of the World, 1989”), is on view in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Alighiero Boetti died of a brain tumour in Rome in 1994 at the age of 53.

-

TEFAF Maastricht 2024

7 - 14 Mar 2024We are looking forward to seeing you at TEFAF Maastricht 2024! On this occasion our booth will showcase a selection of historically relevant paintings, sculptures...Read more -

Arte e Collezionismo, Rome

ML Fine Art is pleased to invite you to visit us at Arte e Collezionismo art fair in Rome. 29 Sep - 2 Oct 2023ML Fine Art looks forward to seeing you in Rome. On this occasion our booth will showcase a selection of historically relevant paintings, sculptures and...Read more -

NOMAD 2021

8 - 11 Jun 2021ML Fine Art is pleased to announce its participation at NOMAD ST. MORITZ 2021, with a selection of works by Carla Accardi, Alighiero Boetti, Antonio...Read more -

TEFAF Maastricht 2020

4 - 11 Mar 2020We are pleased to announce our participation at TEFAF Maastricht 2020. Our booth will showcase a selection of historically relevant paintings, sculptures and works on...Read more

-

BIAF 2019

Florence International Biennial Antiques Fair 21 - 29 Sep 2019Read more -

Masterpiece London 2019

27 Jun - 3 Jul 2019M&l Fine Art is pleased to participate, for the fourth consecutive year, at Masterpiece London. Our booth featured a selection of historic works by Modern...Read more -

Artefiera 2019

1 - 4 Feb 2019Galleria Matteo Lampertico is pleased to partecipate at Artefiera 2019. Our booth will present a selection of works by Italian artists, including Carla Accardi, Angelo...Read more -

Artgenève 2019

31 Jan - 3 Feb 2019Led by important and historic works by Théodore Géricault, Paul Gauguin, Lucian Freud and Piero Manzoni, M&L Fine Art's booth presented a tightly curated booth...Read more