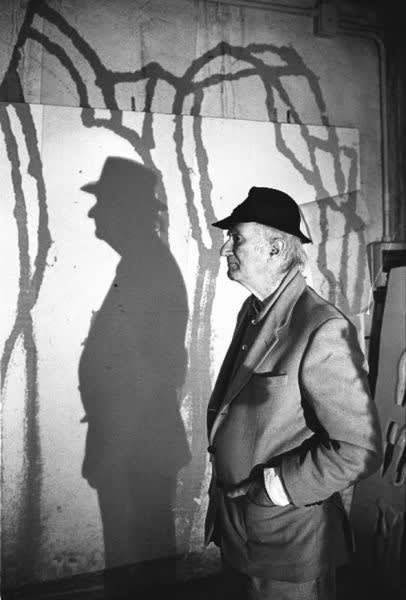

Pietro Consagra Italian, 1920-2005

“I think the path pursued by Consagra in his sculpture is most consistent – each new stage is justified; what is particularly important is the actual, physical expression of his vast concept of space, in the environmental sense – I won’t use the more scientific term ‘ecological’ – through the production of large-scale compositions that are no longer merely proposals or hypotheses of a relationship with space, but truly create a new relationship between the object ant the space in inhabits;… incorporating in the environment works that do not solely mirror it, but alter it. … To me this is one of the most original and novel aspects of Consagra’s work.“

- Giulio Carlo Argan, “Pietro Consagra, un classico dell’arte” (1987), documentary by Antonia Mulas

Born in 1920 in Mazara del Vallo (Trapani), Pietro Consagra studied at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Palermo. Driven by the need for closer contact with the “pulsating heart of creativity”, in 1944, he moved to Rome, which had recently been liberated by the American landing forces. Here he made friends with the artists Turcato, Mafai, and Guttuso (with whom he briefly shared a studio in Via Margutta 48).

In December 1946 Consagra travelled to Paris, where he visited the home of Pevsner, and the ateliers of Brancusi, Giacometti, Laurens, Hartung, and Adam (who had many plaster casts of Picasso’s sculptures). He also struck up a friendship with Gildo Caputo, director of the Galerie Billier, and with Alberto Magnelli. Back in Rome, Consagra’s urge to break new ground became even stronger. Together with Accardi, Attardi, Dorazio, Mino Guerrini, Perilli, Sanfilippo and Turcato, on 15 March 1947 at the studio in Via Margutta, Consagra composed the manifesto that was to be published in the first issue of Forma magazine, in which the artists declared themselves to be “Formalist and Marxist”, and took a stand against Picasso’s distortion and metaphysical romanticism, in the name of “Abstractionism”. For the newly formed group, this was the only language able to bring about a profound renewal of artistic expression.

In October 1947 the founders of the Forma group (Consagra, Dorazio, Guerrini, Perilli, and Turcato) held their first exhibition at the Art Club gallery in Rome; meanwhile Accardi, Attardi, and Sanfilippo showed their works at the Galleria Mola in November. In the Art Club’s bulletin of December 1947/ January 1948, Enrico Prampolini wrote that “the large, vertical composition by sculptor Consagra makes him the only one of his colleagues to achieve a self-sufficient form of entirely abstract expressionism“.

Together with Arp, Brancusi, Pevsner and others, in 1949 Consagra exhibited at the Mostra di Scultura Contemporanea, curated by Giuseppe Marchiori, in the gardens of Palazzo Venier dei Leoni (Peggy Guggenheim Foundation) in Venic; on this occasion Peggy Guggenheim made her first acquisition of a large-scale work by Consagra for her collection.

In 1952 Consagra wrote an essay entitled Necessità della scultura, taking a stand against the pessimism expressed in La scultura lingua morta (1945) by Arturo Martini, who had not taken the path of Abstractionism. Consagra felt an almost moral need to free sculpture from its three-dimensional character, which, according to him, implied an authoritarian centre. His frontal vision surfaced as a richly potential alternative; it meant ridding sculpture of its burdensome historical legacy – to his mind now redundant – and bringing it to essential concepts, in the belief that putting the object directly in front of the viewer would establish an instant dialogue.

As Consagra himself wrote: “The frontal placement as a different outlook was fundamental for me to continue being a sculptor. I discovered that shifting away from the centre was more important to me than sculpture itself: placement became meaning. By introducing placement itself as a component of plasticity, I could observe sculpture in a way that would otherwise have remained unrevealed”.

Invited to hold exhibitions in Europe and in North and South America, Consagra established himself with an unmistakable form of sculpture that defined a philosophy of surface – surface that is neither smooth nor volumetric, but constructed with juxtaposed or overlapping planes – which, like a screen, established a spiritual dialogue in the observer and a synchronic perception of the object. Colloqui (“Colloquy”) is in fact the title given to the series of bronze sculptures and he produced from 1952 onwards, which were presented at the 1954 and 1956 Venice Biennale. In the same Venice Biennales he presents also Legni Bruciati (“Burnt Woods”) by 1954 and 1956. With their single point of view and their powerful, expressive psychological abstraction, there works established the subjective logic of a “more direct, frontal relationship with the viewer, a têtd-à-tête”.

His participation at the 1955 Biennal in São Paulo (where he was awarded the Prize “Metallurgica Matarazzo”), and a personal room at the 1956 Venice Biennale – where he exhibited a bronze “Colloquio”, and his “Legni bruciati” (“Burnt Woods”), a great many of which were acquired by American collectors and museums – won him international recognition. At the same Biennale he was awarded the Einaudi Prize for his contribution to renewing the concept of sculpture. In 1958 he received the Honorable Mention of the Canergie Institute in Pittsburgh and in 1959 the Prix de la Critique Belgique in Brussels.

Following his solo shows at the Palais des Beaux Arts in Brussels (1958), the World House in New York (1958), and the Galerie de France in Paris (1959), Consagra also exhibited at the Documenta II in Kassel in 1959. The following year he had another personal room at the 1960 Venice Biennale, where he was awarded the Prix for Sculpture. As Nello Ponente wrote, though European in outlook, Consagra’s creative adventure was such that “no other sculptural oeuvre can stand alongside it, there is no comparsion“.

In 1962 the Editions du Griffon in Neuchatel published a monograph with texts by the eminent art historian Giulio Carlo Argan, translated in four languages. That same year, Consagra exhibited at The Solomon Guggenheim Museum in New York, and participated in Documenta III in Kassel in 1964.

With the advent of Pop Art, Consagra entered a periodo of self-questioning, during which he began working intensely with enamel paint, which brought him to a significant turning point: the coloured and bifrontal sculpture of the Piani Sospesi (“Suspended Planes”, 1964-1965). In there work, and in the series of Ferri trasparenti (“Transparent Irons”) of 1965-66 – pink, yellow, violet, blue, white and turquoise sculptures with curved contours and planes that fragment and swell as if levitating – the conceptual tension of the firsts Colloqui gives away to the sensuality of a more extrovert language. The ensuing solo exhibition in 1967 at the Museum Boymans van Beuningen in Rotterdam testified to the burst of creativity of this new period, which was discussed in the critical presentation by Maurizio Calvesi in the catalogue.

In August of that same year Consagra flew to the United States, where he stayed for a year. He taught at the School of Arts in Minneapolis, and was invited to take part in the Sculpture from Twenty Countries exhibition at the Solomon Guggenheim Museum in New York. He also had a solo show in October 1967 at the Marlborough Gerson Gallery, New York, where he presented the Ferri trasparenti, Giardini (“Gardens”, 1965/66) and the Piani appesi (“Hanging Planes”, 1966/67). In the interview that appeared in the catalogue, Consagra himself explained to Carla Lonzi: “The images are no longer differentiated and within the square framework, now a spiral vector generates a single image. With the spiral I move from the inside towards the outside, and from the outsider I seek to return inside again: to me this is like breathing“.

The emotional mobility of these revolving Ferri trasparenti was a prelude to the subsequent introduction of bifrontality, an element that doubled the point of view.

Colloquio col vento (“Colloquy with the Wind”) of 1962, also revolving and elaborated on two fronts with its peeling planes, already had this character. Subsequently, in the book “La Città Frontale” (“The Frontal City”, written in 1968 by Consagra and published the year after, two Spessori (“Thicknesses”) from 1967 were reproduced: bifrontal sculptures in aluminium, executed before his journey to the United States, alluding to the male and female sex, conceived together in material of the same thickness 820 cm) and height (30 cm), therefore with equal impact. After an interesting new analysis of the stone bollard – those masterpieces of Renaissance architecture, symbolising virility as an intimidating form of power – in the same book Consagra highlighted the fact that, in the said Frontal City, virility is not “terroristic”, but “proportionate to the desire of coupling with the person of one’s choice”, on an equal standing, as foreshadowed by the unusual pair of Spessori.

In the new Sottilissime (“Extremely Thins”) of 1968, the artist experimented with the minimum thickness of a bifrontal work, making the plane two-tenths of a millimetric thic. At less than a tenth of a millimetre, the sheet fails to remain upright and bends, hence the Sottilissime impossibili. At the same time Consagra conceived, the Edifici frontali (“Frontal buildings”) of 1968, made in steel ot the maximum thickness possible in a bifrontal work (six meters), enveloping inhabitable forms in the shape of a “continuous band” with no right angles. The new Frontal City would offer a new relationship among its inhabitants, and a form of architecture that was an artwork in space, of a “mobile, temporary, transparent, paradoxical” nature, allowing for changes in choice.

Before leaving the States, in May 1968 Consagra executed a final work for the offices of General Mills in Wayzata, Minnesota: Solida e trasparente (“Solid and Transparent”), a large bifrontal work with sinuous forms, through which the setting beyond can be glimpsed.

In 1969 Consagra began to work in Milan, too. By 1972, Consagra’s continuing meditations on the issue of thickness with regard to frontal placement, and the possibility of thereby increasing the solidity of the large-scale bifrontal sculptures, prompted him to begin using marble, owing to its variety and colour. There followed such works as Pietre Matte di San Vito ("The Crazy Stones of San Vitus," 1972), as simple as archetypes, which he presented at his one-man show at Palazzo dei Normanni in Palermo in 1973; while the subsequent exhibition held at Museo di Castelvecchio in Verona in 1977, featured his lively Muraglie (Walls) of 1976, large-scale marble works. Both exhibitions were curated by Giovani Carandente, in tandem with Licisco Magagnato in Verona.

From the time of the browns of Legni bruciati of 1954 to Ferri trasparenti, colour had already been characterising element of Consagra’s sculpture. But the preciousness of the sculptures in marble, coupled with the de-substantialisation typical of the frontal viewpoint, presented a challenge that the artist met through controlling his temeprament, thus producing sculpture that was articulated, rigorous yet hedonistic. As hedonistis as it could be for a Sicilian man who aimed to stray outside his geographical confines, in order not only to be Mediterranean but to initiate a culture of imagery “that expresses itself so autonomously that it constituted an opposition”, as Carandente observed.

In 1983, in the town of Gibellina, built after the Belice earthquake in 1967, Consagra executed Meeting, his first frontal building in masonry, iron and glass, based on a 1972 project, whose continuous profile follows the support structure, and instead of staircases it has sloping walkways. In 1972, he had also designed a transparent Theatre with a bifrontal stage and two seating areas facing each other, so that the spectators could also look at one another. Building began in 1992.

“Consagra is even more sensitive to the problems of the surrounding space than Picasso and Boccioni“, wrote A.M. Hammacher, of the Muraglie and the Addossati of 1976, and of the Porte of 1990 and the Facciate on 1996, in which Consagra compared two different perspectives and two opposing horizon lines in his vision immediately external to bifrontality. What remained unchanged in his work was the process of adding and linking elements essential to each other in a single image, a factor that was typical also of large-scale works destined for the city, like Stella di Gibellina of 1982, a steel sculpture twenty-eight meters high, and Porta del Cremlino n. 10 (“Kremlin Gate n.10”) of 1990, a six-by-eight metre sculpture in red Verona and Botticino marble. These were examples of his sculpturest that had to be traversed. In 1984 he received the Antonio Feltrinelli prize for sculpture, from the Accademia dei Lincei in Rome.

In 1989 the Galleria Nazionale dell’Arte Moderna in Rome devoted a major retrospective to the artist, curated by Anna Imponente and Rossella Siligato, with a contributions in the catalogue by Rudolf Harnehim, Augusta Monferrini, and others.

Consagra died in Milan in 2005

-

NOMAD 2021

8 - 11 Jun 2021ML Fine Art is pleased to announce its participation at NOMAD ST. MORITZ 2021, with a selection of works by Carla Accardi, Alighiero Boetti, Antonio...Read more -

Masterpiece London 2019

27 Jun - 3 Jul 2019M&l Fine Art is pleased to participate, for the fourth consecutive year, at Masterpiece London. Our booth featured a selection of historic works by Modern...Read more -

MIART 2019

5 - 7 Apr 2019Galleria Matteo Lampertico is pleased to partecipate at Miart 2019. Our booth will present a selection of works by Italian and International artists, including Pietro...Read more -

Miart 2017

31 Mar - 2 Apr 2017Read more