-

-

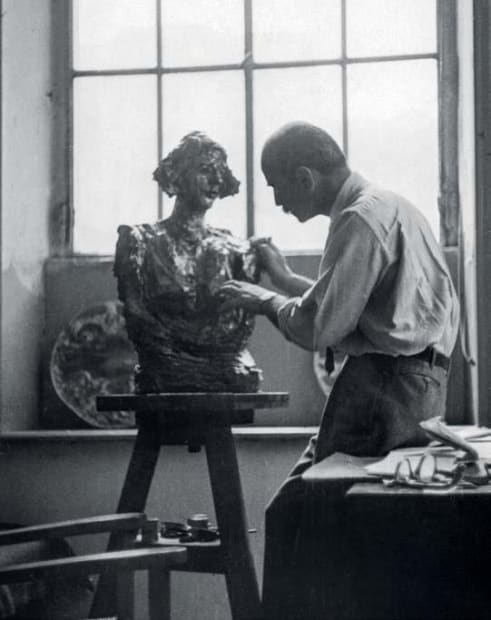

Lucio Fontana working on a portrait of his wife Teresita, 1949 ca.

-

Lucio Fontana, Vongola e corallo, 1936. Glazed ceramic, 17 x 31 x 23 cm

Lucio Fontana, Vongola e corallo, 1936. Glazed ceramic, 17 x 31 x 23 cm -

Lucio Fontana, Testa di Medusa. 1948-1954. Glass paste, mosaics and cement on metal frame, 190 x 189 cm. Installation view: "In Part," Fondazione Prada, Milan, 9 May – 4 Nov 2015. Photo Attilio Maranzano

Lucio Fontana, Testa di Medusa. 1948-1954. Glass paste, mosaics and cement on metal frame, 190 x 189 cm. Installation view: "In Part," Fondazione Prada, Milan, 9 May – 4 Nov 2015. Photo Attilio Maranzano -

Lucio Fontana working on ceramics, 1950s, gelatin silver print. Courtesy Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Milan

-

-

Lucio Fontana in his via De Amicis studio, Milan, 1933. From left: Busto di Signorina, Uomo Nero, Uomo seduto (or Atleta in Attesa o Discobolo) © Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Milano by SIAE

Lucio Fontana in his via De Amicis studio, Milan, 1933. From left: Busto di Signorina, Uomo Nero, Uomo seduto (or Atleta in Attesa o Discobolo) © Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Milano by SIAE

Lucio Fontana, Crucifix, 1949: Glazed ceramic, 58 x 26.5 x 8.5 cm

Past viewing_room