-

-

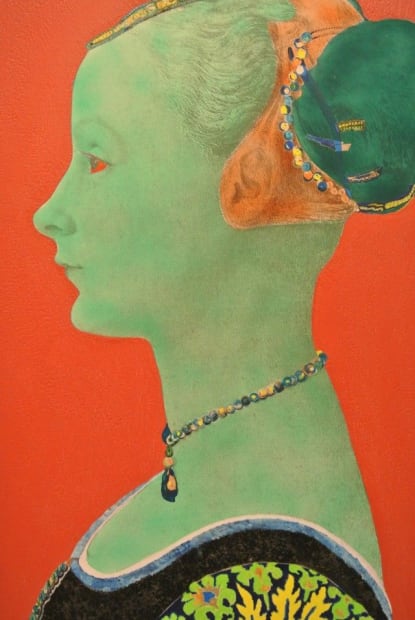

Martial Raysse

Monica Vitti, 1963

(i) Signed on the reverse; Signed twice, titled, dated and inscribed on the stretcher

(ii) Signed, titled, dated and inscribed on the stretcher

(i) Xerographic painting on canvas

(ii) Xerographic painting, laminated on canvas, gilded metal brooch with eight green plastic beads directly pinned

on canvas

(i) 27.5 x 22.2 x 3 cm

(ii) 24.5 x 16 x 3 cm -

Martial Raysse, Portrait of an Ancient Friend, 1963, Pinault Collection

-

Monica Vitti by Peter Basch, Rome, 1960

-

Martial Raysse (1961) photo by Harry ShunkMartial Raysse (1961) photo by Harry Shunk

Martial Raysse (1961) photo by Harry ShunkMartial Raysse (1961) photo by Harry Shunk -

La galleria di ritratti femminili di Martial Raysse è diventata iconica: Brigitte Bardot serigrafata in colori contrastanti, Anne Wazamesky che sembra la Gioconda e modelle della cerchia dell'artista con le fattezze dell'Odalisca di Ingres o della Giovanna Tornabuoni del Ghirlandaio. Dalla serie Made in Japan (1964) alle grandi composizioni pittoriche come Dieu Merci (2004), Raysse sottopone il genere tradizionale del ritratto a un filtro kitsch, conferendo ai volti presi in prestito dal mondo del cinema e della storia dell'arte un carattere artificiale. Le pin-up e le eroine teatrali vestite in costume, mascherate con un trucco spesso o dietro una maschera, e che indossano accessori di bellezza sono come sfingi provocanti ed enigmatiche.Raysse si concentra sullo stereotipo della bellezza femminile presentato nelle riviste di moda dell'epoca. Utilizza spesso il ritratto di sua moglie France e le immagini di donne che trovava nelle pubblicità, sulle copertine delle riviste e sui cartelloni pubblicitari giganti. Immagini che venivano copiate da centinaia di giovani donne che volevano conformarsi a questo ideale. Raysse modifica queste immagini enfatizzando il trucco e gli oggetti di bellezza. Truccata pesantemente con rossetto, glitter e cipria, l'identità della donna dietro la pubblicità viene oscurata e trasformata in un personaggio standardizzato. Questo approccio alla Pop Art si differenzia dal lavoro dei suoi contemporanei, come Andy Warhol, che si concentrava su individui noti e icone del suo tempo.

I volti femminili che Martial Raysse sceglie più spesso di raffigurare nelle sue opere dei primi anni Sessanta sono quasi anonimi, come le immagini che compaiono nei manifesti, nelle vetrine e nelle riviste dell'epoca. Riconosciamo quasi occasionalmente i volti delle attrici: Sophia Lauren, Marilyn Monroe, Brigitte Bardot e, in questo caso, Monica Vitti (il cui ritratto è stato dipinto anche dall'artista britannica Pauline Boty nello stesso anno, il 1963).

Icona del cinema italiano degli anni Sessanta, Monica Vitti divenne nota per i suoi ruoli nei film di Michelangelo Antonioni (con cui visse per dieci anni), e in particolare per L'Avventura, La Notte e L'Eclisse. Il volto dell'attrice è presentato come un dittico, diviso in due parti. A sinistra, la star si riconosce subito per il suo sguardo e il suo lieve sorriso. A destra, si vede solo la nuca e un orecchio, ornato da un ricciolo di piccole perle di plastica verde che rappresentano un grappolo d'uva. L'artista si è basato su un'immagine stampata da una rivista dell'epoca, utilizzando tre colori vivaci come un trucco per enfatizzare la grazia singolare dei lineamenti di Monica Vitti: il verde per l'iride degli occhi (la stessa tonalità di verde che Antonioni sceglierà un anno dopo per il grande cappotto che l'attrice indossa in Le Désert Rouge), una striscia di arancione fluorescente e un blu profondo e luminoso per le palpebre e lo sfondo (che ricorda il blu tanto amato da Yves Klein, membro del gruppo dei Nuovi Realisti, come Raysse). I contorni degli occhi sono sottolineati da una linea nera, che aggiunge intensità e mistero allo sguardo del soggetto. Come un'ode alla sua bellezza, allo scintillio e all'abilità, Monica Vitti testimonia in modo abbagliante i principi alla base del lavoro di Martial Raysse: "I miei quadri sono un po' come un esorcismo. La nozione di morte deve essere bandita, la nostra fiducia deve essere riconquistata. Attraverso il lavoro, attraverso la bellezza" (Martial Raysse citato in "Martial Raysse, Première Partie: l'esthétique" di L. Brown, pubblicato da Zoom, Parigi, 1971).

Martial Raysse, Monica Vitti, 1963

Past viewing_room